A Critique of Architectural Modernism

Taking a look at Le Corbusier’s autistic five-point manifesto

In the previous article, we explored traditional architecture and examined what our innate appreciation for classical beauty reveals. Now, we turn to its opposite—Modernism and its successors.

Why is Modern architecture so ugly and sterile? Why do most people instinctively detest it? If only architects claim to appreciate its supposed merits, does that make all other intellectuals—musicians, art historians, philosophers—unsophisticated plebs?

Most architects will roll their eyes at these questions. Yet they fall silent when reminded that some of the most scathing critiques of the Modern Movement came from within its own ranks. Critical Regionalism, Brutalism, Art Deco, Postmodernism and Tectonism all emerged as reactions against Le Corbusier’s manifesto.

So, what exactly goes on in architects' heads? Why the obsession with mutilating cities with three-dimensional graffiti? Before diving into Le Corbusier’s Five Points, it's crucial to note that the first Modernists—Gropius, Corbusier, and Mies van der Rohe—operated on a total inversion of the Cosmic Law (see previous article).

All those natural intuitions we discussed—expecting a building to be ‘rooted,’ to have a ‘main body’ and a ‘crown,’ to align with gravity and tectonic logic through a central entrance and symmetrical solid corners—were seen as arbitrary limitations that technology could finally liberate us from. While classicism was perceived as absolutist and totalitarian, Modernism was presented as “a modern, harmonious, and vibrant architecture, the visible sign of an authentic democracy” (Gropius). Industrialisation and machine logic, rather than being viewed as threats to organic culture, were embraced with naïve optimism. As Corbusier ecstatically proclaimed, “A house is a machine for living in.”

So, without further ado, let’s delve into Corbu’s rather idiosyncratic scribblings. While reading this, take a moment to look at the image below. It shows Villa Savoye, a sterile building that reflects all five points in Le Corbusier’s Manifesto.

Le Corbusier's Five Points of Architecture

1. Pilotis

Buildings were to be lifted off the ground on stilts, freeing up space for cars and pedestrians. Instead of solid foundations and a clear sense of grounding, architecture now signified weightlessness and detachment. Where people instinctively expect tectonic stability, they’re given its negation.

2. Free Plan

Load-bearing walls were to be eliminated, leading to formless, open spaces that blurred distinctions between inside and outside. The result? Confusion, disorientation and a sense of exposure rather than shelter. What architects see as ‘liberation’ only alienates the inhabitants.

3. Free Façade

With structure and ornament stripped away, the building’s face either became an abstract minimalist sculpture or disappeared entirely behind glass curtain walls. The result? A grotesque mishmash of exposed pipes and distorted reflections of neighbouring buildings, marketed as “respect for historical context.”

4. Horizontal Windows

Continuous ribbon windows maximized uniform lighting but destroyed the vertical rhythm that ties traditional streets together. Classical architecture’s subtle variations create harmony; Modernism’s relentless horizontality imposed a mechanical sameness.

5. Terrace-Garden

Traditional roofs—vaults, arcades, protective eaves—were abandoned in favour of flat terraces. The result? Constant leaks (as seen in Villa Savoye) and a bizarre Near Eastern aesthetic applied universally, without consideration for local climate or geography. Where people expect to see the "crown", the arcade, the vault, the roof that closes and protects the interior shelter, they’re practically being trolled by the architect.

Modernism as Ideology

While reading these points, you must have noticed some parallels with The Current Year. Le Corbusier’s manifesto is ‘diversity is our strength’ expressed through a different medium.

First principle - free circulation instead of rootedness. ‘No papers. No borders. No person is illegal.’

Second principle - questioning spatial boundaries, blurring and subverting ‘problematic’ distinctions like inside vs outside. Replacing the reactionary ‘closed room’ with the progressive inviting ‘open space’.

Third principle – a building’s exterior envelope stops being a ‘facade’; it is no longer tied to structure or decoration. Progressives love this sort of subversion – dismantling a coherent whole, reducing it to its parts and celebrating this as some great liberation victory. ‘Gender has nothing to do with sex’, ‘Ornament is crime’ (Adolf Loos), ‘Stop objectifying body parts’ etc.

Fourth principle – continuous horizontal windows are a good metaphor for the progressive fixation on imposed equality, the rejection of tradition and polite manners in the name of individual self expression. ‘Everything I say or feel is valid and it must be heard’ etc.

Same Logic Applied to Whole Cities

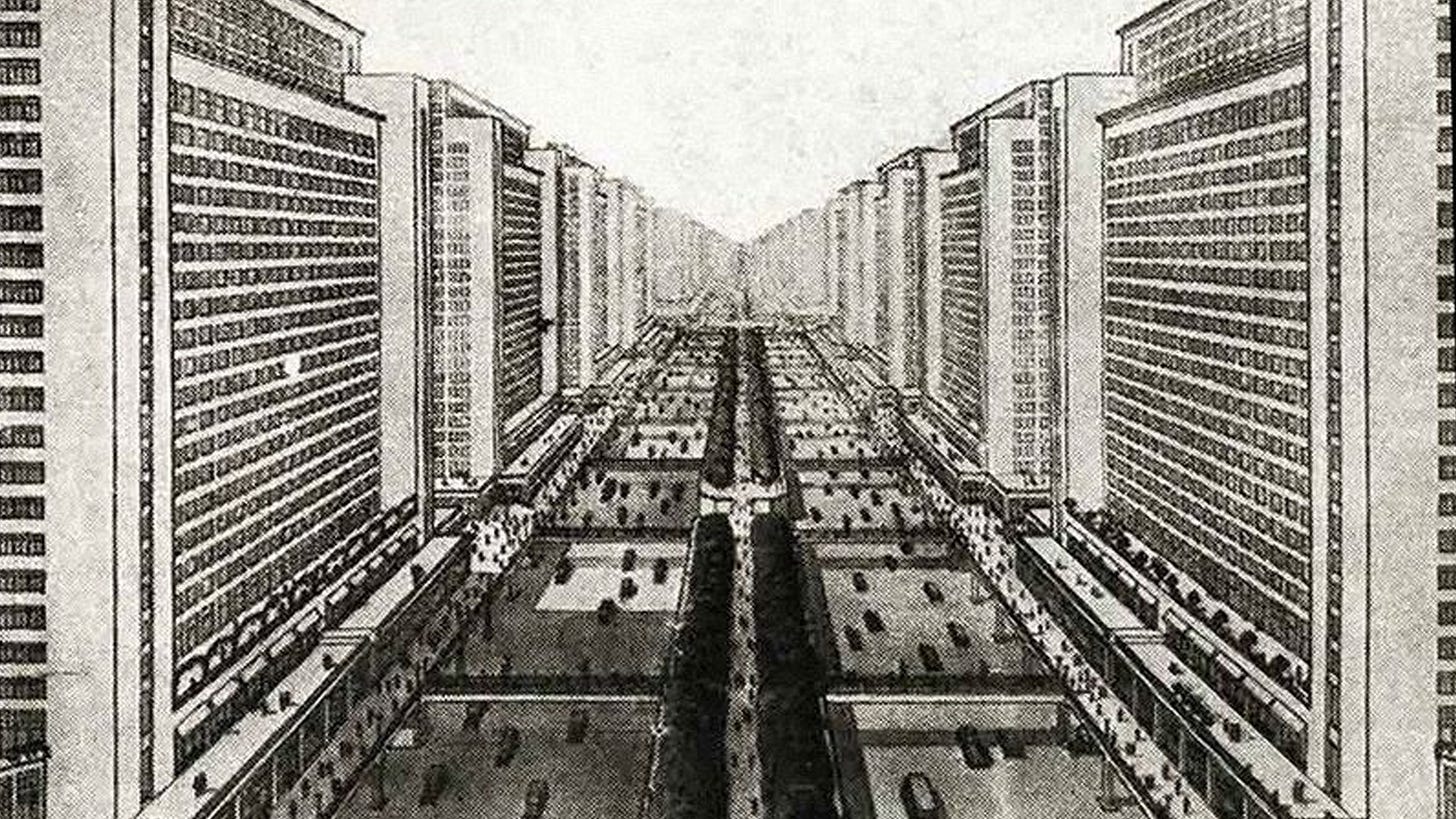

Le Corbusier’s Plan Voisin extended these principles to the entire city (the madman was hoping to replace a large area of central Paris with his monomaniacal towers and traffic arteries). His proposal split the city into five functional zones:

Residential: Repetitive high-rise blocks (he unironically called these ‘dormitories’)

Commercial: Offices stacked like sardines

Industrial: Factories at the outskirts

Transportation: Roads and railways

Green: Rectangular parks

Traditional streets with coherent façades were thus abolished in favour of disconnected towers surrounded by open space, severing urban life from its historical and communal roots.

We can conclude that the entire project of the pioneers of Modernism—Corbusier, Mies, Gropius and their followers—was one of extreme subversion, all in the name of meaningless abstract principles. Once you've abstracted the local inhabitant into "Universal Man," the home into "living unit with day-night separation," the city into clinical functional "zones", any aesthetic or spiritual considerations cease to exist. The organic logic of traditional cities cannot justify itself by appealing to the new set of abstract principles.

Technological constraints further sealed architecture’s fate—industrialisation, standardisation and prefabrication reduced building to a purely mechanical process. A few decades later, the rise of CAD and parametric design made sure everyone was designing the same slop. Architecture thus becomes completely indifferent to any notions of Beauty or Cosmic Law; and in doing so, it becomes incredibly ugly.

What Comes After Modernity?

Rather than recognizing their failure, most architects double down, retreating into professional solidarity and insular jargon. Their contempt for the public—the very people forced to live in their inhuman spaces—is palpable. From the posture of self-anointed elites, their disdain for plebs makes them write walls of apologetic text on social media only their colleagues bother to read. ‘The left can’t meme’ is perennial.

There’s no saving Modernists from their own dogma. But we can expose the lie that their ideas were ever functional, rational, or necessary. Modernism wasn’t progress—it was ideology masquerading as pragmatism. Theorycels getting high on their own supply.

Feel free to share this with your friends; it might help some architects with based views realise that no one’s forcing them to cling on to these meaningless abstractions.

We are part of what follows after Modernity. The seed that will grow from these ruins. What strategies can we employ to start building new structures, new architecture, new institutions that would help our people get together and thrive?

Go ahead! Achieve all your goals! Break all the dams! Faster! You are unbound. Go ahead and fly with faster wings, with an ever greater pride for your achievements, with your conquests, with your empires, with your democracies! The pit must be filled; there is a need for fertilizer for the new tree that will grow out of your collapse.

— Revolt Against the Modern World, J. Evola

The smugness and the superiority we felt when proposing to normie clients terraced roofs. As if we knew some secret from the future and were willing to share it with the plebs. And each time the client stuck to its pitched roof, felt like a defeat. Soon I learned to follow the client more, but then felt like losing the whole purpose of enlightening the masses.

The CAD didn't help much, au contraire, the easiness of copying and pasting, and the difficultness of drawing anything but simple geometry made it so "everybody" could do it. Much like LLM's now, the CADs seemed to stealthily facilitate the dumbing down. I for one felt for the whole minimalist trend out of comfort ultimately. Expediency. Efficiency.

I then felt like everybody should have been given the tools to design for himself. Small projects to be excused of not hiring an architect. Democratization. For a supposed return to the vernacular. But apparently once the virus of modernity has been deployed, you can't unbake the cake. No more vernacular as we understood it, built on solid foundations. The new vernacular is just mutants of modernity. So everybody can design anything and nobody apparently really can.

Brasilia is a good example of the results of modernism. The town is hostile towards pedestrians and the buildings are hostile to humans. Walking in niemeyer's buildings is a physical and psychological ordeal, the white cement reflects light and heat from all angles, its like being inside a solar oven, trees are non existent and shadow is rare. The inside of the buildings aren't better, the huge windows let too much sun and heat to penetrate, so they need to tint the windows with strong shading to make the space minimally habitable.