Traditional Architecture and the Cosmic Order

Why we instinctively prefer the beauty of the past

In an earlier post, I noted that people intuitively find traditional architecture beautiful. Yet, in typical midwit fashion, architects dismiss this instinctive response as 'reactionary' and entirely unfounded. In this post, I’ll do the opposite and explain how our instinctive appreciation for classical beauty reveals the most valuable thing a culture can offer: a reflection of divine order.

Metaphysical Order

All past civilisations – archaic, classical, medieval – shared this bonkers notion that the world they inhabited was a harmonious whole, reflecting the timeless realm of the divine, constantly animated and sustained by it. They discerned the subtle presence of the Sacred everywhere; they also echoed it in all their buildings and institutions. If you're familiar with this sacramental perspective, it's because you've likely had your own encounter with the Sacred in one way or another.

Try explaining it to a normie, though, and watch their eyes glaze over. In modernity, metaphysics has been swapped for a mechanistic view of the Universe, seen as an lifeless expanse governed by physical equations. Through blind chance, human reason (or its illusion) just ‘emerged,’ leaving us as the only conscious observers of an inert but ever-expanding cosmic machine. These assumptions underpin every leftist ideology. They also gave us the soulless, mass-produced slop that now defaces our cities.

Pre-moderns believed in a Cosmic Law, not as a ‘code’ or ‘equation’, but as something active and alive, the pattern of God’s essence permeating everything.1 Truth, Goodness and Beauty weren’t just arbitrary thoughts, they described reality itself, where matter aligns with spirit, working as a complete whole. Beauty, in particular, was tripartite, being composed of integritas (wholeness), proportio (harmony of parts) and claritas2 (intelligibility).

In this worldview, anything considered real or significant had to reflect the Sacred or the Cosmic Law. Buildings and towns weren’t just structures; they were literal icons (imago Dei), fractals manifesting the sacred pattern and the relation between its parts.

Naturally, this meant that boundaries weren’t seen as obstacles to overcome through technology, but as intrinsic to harmony. Traditional and classical techniques of building coexisted with limits and boundaries, they even respected or celebrated them. This is why every vernacular or classical style reflected its geographic location instead of denying it.

Gravity is not your enemy

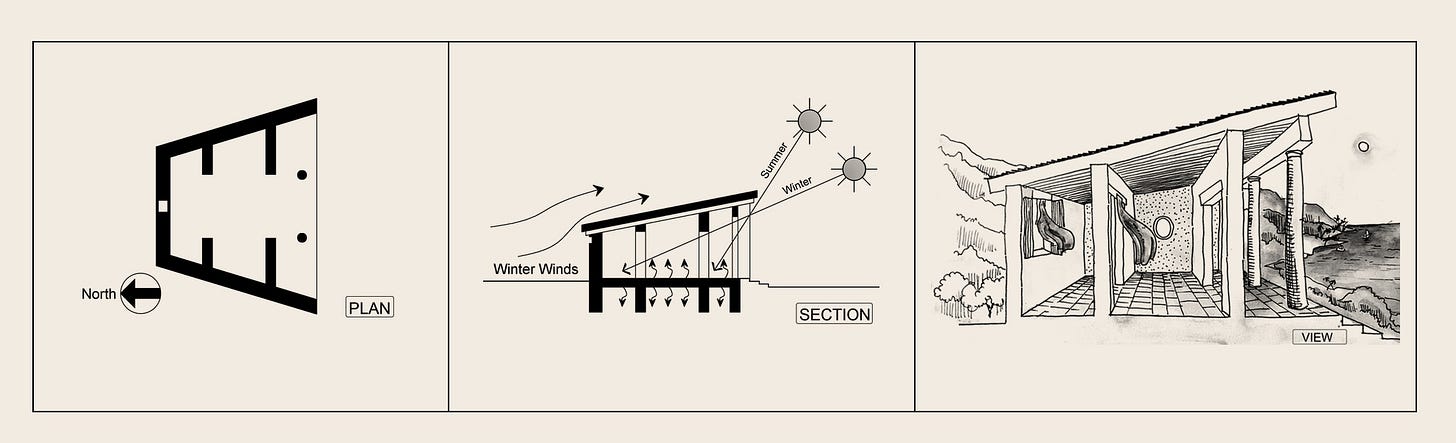

In virtually all pre-modern architecture, buildings engaged harmoniously with atmospheric elements—wind, snow, rainfall—showing them a form of deference. The roofs’ angles adapted to their location, interiors protected from the cold in winter, while making natural use of ventilation in summer, windows made perfect use of sunlight in all seasons (Socrates’ megaron), etc.

A building’s ground floor was always sturdy and protective like roots of a tree or a pedestal. The main floors formed the "body" of the building, much like a tree trunk or a human torso. The uppermost floor expressed the crowning and sheltering logic of the building, akin to a tree’s canopy, a hedgehog’s spines or a warrior’s helmet.

In classical learned architecture, these principles were not only preserved but celebrated and ennobled, as stonework embraced the same motifs that were once sculpted in wood.

The solidity of the ground floor was reinforced through rusticated stone, heavy cornices and bossed masonry. The middle floors were decorated with colonnades, pilasters and rhythmic bays, framing windows and balconies. The upper level was adorned with architraves, decorated roofs or arcades to reinforce the crowning effect.

Horizontally, traditional buildings featured a clearly defined central entrance, while corners were reinforced to transmit stability. In classical architecture, entrances were marked by porticos and decorative canopies, while corners were often accentuated with extra columns or rusticated quoins to reinforce the perception of tectonic stability.

The Urban Microcosm

Historic towns possessed an organic character, a hierarchy of spaces and a gradation from public to private, from Sacred to profane.

The town centre served as a cosmic axis or a ‘beating heart’, while the boundary—often marked by defensive walls—provided its protective skin. In historical towns, houses didn’t try to be palaces, malls didn’t try to be cathedrals and peripheries didn’t attempt to erase city centres. One might notice a similarity with natural ecosystems3, where every element occupies its niche and contributes to the harmony of the whole.

At the street level, the spaces were shaped to guide people’s perception. They aligned to form unified street fronts, with voids between them defining streets and squares. Street-facing facades showed deference to the public space through richer ornamentation and a sort of dialogue with neighbouring buildings—akin to putting on one’s best attire when going to town.

Urban spaces were organised hierarchically, drawing attention to central edifices. These landmarks were emphasised through scale, verticality (church spires, clock towers), symmetry, proportional harmony and axes of importance.

This visual hierarchy reflected how people participated in civic life. The city centre, visible from all directions, was home to the most important public buildings—cathedrals, royal palaces, town halls and public squares. A little further out were universities, guilds, and marketplaces, which were centres of local activity. Beyond those, residential areas coagulated around parish churches. This public-to-private gradation was mirrored in the logic of homes themselves. Traditional townhouses had a public face (the merchant’s shop at street level), a semi-public space (the parlour on the first floor) and private areas (bedrooms and servant’s quarters).

This entire structuring of towns completely corresponded to the sacramental worldview I described in the introduction. This is why we find traditional cities beautiful at the deepest, instinctive level. People did not start theorising about aesthetic principles before designing their villages and towns; they simply aimed to live close to the Sacred and express this desire through every action the engaged in4.

Aesthetics came later when classical philosophers developed a theory of beauty that remained largely unchanged from Plato, Vitruvius, later Aquinas until the 19th century.

And Then Everything Fell Apart

When modernist bugmen started dismantling this organic metaphysical worldview, they were clueless about the consequences. Under the action of ideologues like Le Corbusier, Mies and Gropius, the Modern Movement pompously proclaimed the death of the ornament in the name of functionalism; it flattened the town’s visual hierarchy under the guise of democracy. It replaced craftsmanship with 'scientific mass production' and rejected a symbolic, sacramental understanding of urban space in favour of rational 'zoning.' In doing so, they unknowingly unraveled the invisible fabric that once held everything together. The results were immensely ugly. But more on that in a future article.

Footnotes

1. ‘The Abolition of Man’ by C.S. Lewis explains this in more detail in chapter1. Audiobook on YouTube.

2. For a summary on Aquinas’s aesthetic theory, check out ‘The World as God’s Icon’ (final chapter, I believe) by my good friend, Sebastian Morello.

3. The ‘nature’ vs. ‘culture’ dichotomy is part of the modern mind virus. For more on this, check out ‘Why Liberalism Failed’ by Patrick Deneen

4. Look up ‘The Sacred and The Profane’ by Mircea Eliade for a study on how archaic peoples founded their towns and villages

Yes! I am working my way through architect Christopher Alexander's 4 vol. magnum opus "The Nature of Order: An Essay on the Art of Building and the Nature of the Universe". I want to know more about how the order in Creation informs the principles in human sub-creations. Ordered beauty is visible, it is objective--I want to know what is behind it!

Sums up nicely much of what I've been ranting on about privately to my family for decades now! The notion of a centrally placed entrance struck a chord. I remember the first time I attempted to find the main door at the Barbican. Non-hierarchical buildings simply don't function. It's almost as though the architect is deliberately wasting our time as a spiteful revenge on an innocent public for the painful consciousness of his (or her) lack of talent.